A young boy conscripted aboard a ship of seasoned sailors. A journey to faraway lands in an uncharted world. A tale of cannibals and exotic creatures and devastating illness. This could be the makings of the latest young adult action thriller. Instead it’s a strikingly illustrated picture book for older readers, piquantly evocative of centuries-old historical events.In “Sailing the Unknown: Around the World With Captain Cook,” the poet Michael J. Rosen (“Chanukah Lights,” “The Hound Dog’s Haiku”) imagines the journal of the real-life 11-year-old Nicholas Young, the youngest sailor aboard Captain Cook’s Endeavour.

We know very little of the real Young, a delinquent forced into service aboard the ship, where one of his jobs was to care for a milk goat. But we do know, tantalizingly, that he was the first on board to spot the coast of New Zealand and, nearly three years later, the first to spy the English coast on the way home. Not bad fodder for a children’s book, especially one written with acuity and imagination. Rosen writes Nicholas’s journal in playfully archaic shorthand, beginning with the first journal entry on Aug. 19, 1768:

“Once there’s a fair Wind,

Endeavour will leave England for a Continent

None has mapped — None knows exists.

She will not return soon — if She returns.”

Nicholas’s adventures would be hard to rival in fiction. At Tierra del Fuego — Land of Fire — he encounters “Strange People” who “wear not even Fig Leaves for Modesty or Warmth,” yet survive the cold by fire alone. There are strong swells as the ship rounds the Cape, and the crew’s spirits don’t lift until the boat hits Tahiti, where the sailors encounter tattoos for the first time (“7 Mates now wear Them forever”). The Maori of New Zealand not only make stew of the crew’s candles and shoes, “They eat foes slain in Battle!” Worms, coral reefs and mosquitoes each wreak their own kind of havoc. Rosen’s shorthand journal entries often read like poetry, as in this entry, on Day 602 of the voyage:

“Winds write a new Mystery — They pinch the Sea,

as if between Fingers, swirling Water Columns skyward.

The Spouts swell and vanish — then only Seabirds.

Endeavour is their Mystery.”

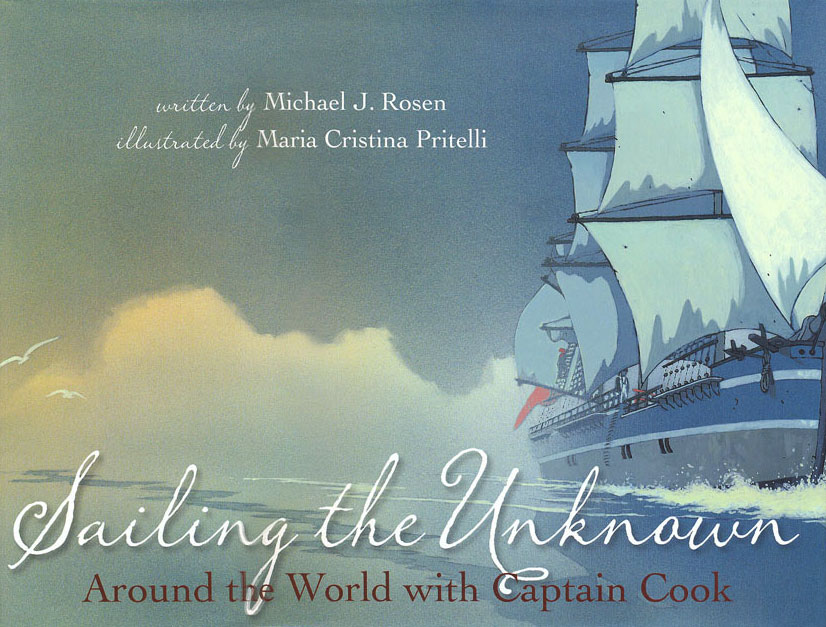

Maria Cristina Pritelli’s illustrations, at once painterly and panoramic, are also intimate and approachable, as if Tintin had been dropped into the tableaus of an 18th-century seascape painter. Some of her scenic acrylics are breathtaking: on the beachfront of “Terra Australis Incognita,” with clouds wavering between land and earth, Aboriginal figures with spears appear on a sunlit strip of liquid sand, their otherworldly shapes silhouetted as they approach the tentative, unwanted explorers. Throughout, the book’s elongated rectangular format creates the impression of forward momentum; its horizontal spreads echo the wide vista at sea. In places, the illustrations are out of step with the text. On one spread, as Rosen describes the stifling heat, the nausea of seasickness, the lice and rope burns and greasy ropes, Pritelli’s cartoonlike spot drawings show the peppy boy beholding the wind, milking the ship’s goat and generally busying himself on deck with a smile on his face.

But for the most part Nicholas’s small-scale figure provides a welcome human perspective to the imposing scale of Cook’s grand circumnavigation. Nicholas’s imagined journals may offer only one tiny window into this great adventure tale, but young readers’ interest will almost certainly be piqued. Next stop: James Cook’s own journals.

By Pamela Paul

The New York Times